Exitosa conferencia de la Dra. Yuriko Saito en el GEAO (Facultad de Filosofía, 2/11/23, Centro Inter. de la US)

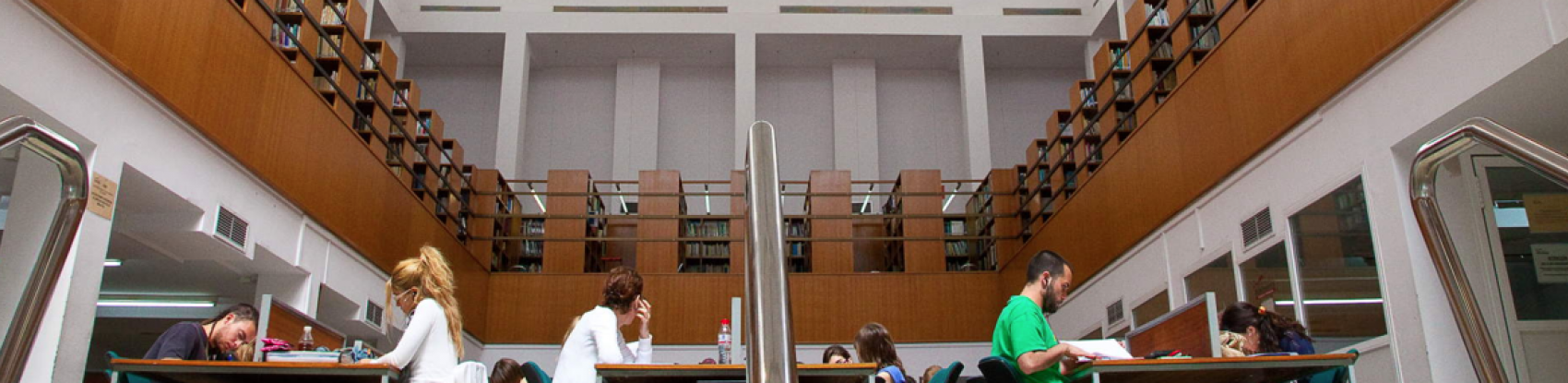

Éxito de público y de calidad en la conferencia de la profª Yuriko Saito: "The Aesthetics of House Chores", impartida en la Facultad de Filosofía de la US, con gran asistencia de estudiantes y profesorado del G.E.A.O., en el Salón de Actos del Centro Internacional de la Universidad de Sevilla:

Fotos: Conferencia Yuriko Saito (Fac Filos US) 02-11-23

facultaddefilosofíainforma2023

The Aesthetics of House Chores

Yuriko Saito

Presentation at Seville, 02 Nov. 2023

Doing house chores dominates our management of everyday life. We clean the floor, dust furniture, wash dishes, do laundry, put things away, and repair broken objects on a regular basis. Most of us would rather not perform these tasks because they are considered tedious, and sometimes backbreaking, drudgery and requiring no creativity or imagination. Thus, they have been traditionally relegated to women and marginalized populations whose work remains invisible and receives little accolade.

Some art projects help shed light on the invisibility of housework and similar tasks, such as street cleaning, yard work, and garbage collecting. While they help raise consciousness and bestow more dignity to these detested works, most of us remain spectators of these art projects. We may develop an aesthetic appreciation of the artistic depiction of such tasks, but it is not clear whether these art works encourage an aesthetic experience of housework itself which we ourselves perform.

Furthermore, the aesthetics of house chores sounds like an oxymoron. Their generally negative aesthetic associations, such as being dirty, messy, smelly, and imperfect, seem to compromise their place in the aesthetic domain, except to create unpleasant experiences. The results of cleaning, washing, straightening out, and repairing may provide a somewhat pleasant experience, but some may question its aesthetic value because it does not compare to the typical aesthetic experiences generated by art and nature. The discourse on housework is also dominated by first-person accounts of those who perform these tasks guided by some practical goal. As such, house chores do not fit comfortably into the quintessential model of aesthetics which is object-centered, judgment-oriented, and disinterested spectator-driven.

This presentation argues against these presumed disqualifiers for according an aesthetic status to house chores and develops a proactive support for the aesthetics of house chores, without unduly romanticizing or glorifying them. Specifically, although it is considered to be a tedious routine without much thought involved, performing house chores can offer opportunities for imaginative and creative engagement with the world around us. We exercise agency in creating the desired effect, whether it regards a cleaned room, laundered and ironed shirts, or mended socks. We handle tools and materials with specific body movements informed by embodied knowledge and skills, following various aesthetic judgments and decisions.

Furthermore, performing house chores also helps cultivate sensibility, respect, and humility toward the material world with which we need to work and appreciation of the material world’s service to us. Tools used in house chores, ranging from a knife and a mop to a vacuum cleaner and a clothesline, are generally taken for granted as the Heideggerian “ready-to-hand” and garner our attention only when they malfunction or break by asserting their “present-athand.” However, there is another way of experiencing them as our faithful companions who help with our tasks which in turn requires our care and maintenance.

Finally, when the beneficiaries of house chores include not only oneself but also loved ones, such as family, housemates, and houseguests, performing those chores can be imbued with affections and memories, thereby enriching the experience. It can be a meaningful experience invested with love and commitments, instead of a mechanical tedium. If the technological advancement frees us completely from performing house chores, such as with self-cleaning and self-repairing materials or robots with artificial intelligence, it benefits the society by reducing the site of exploitation, in light of the fact that these tasks have traditionally been relegated to women of the household and the marginalized and oppressed populations. However, we also need to be cognizant of the loss incurred by depriving ourselves of the traction, and sometimes friction, felt when working with the world. It is because the aesthetics of performing house chores ultimately reminds us of our intimate connection to the world around us and the relational mode of being-in-the-world.

* * *